In a prior article I mentioned the two individuals who first made me aware of elements of Preterism in Orthodoxy: Conley, a Futurist (or Partial Preterist? I can’t really tell), who was citing Vaughn, a full Preterist.

Vaughn had originally brought up this prayer from the Anaphora, a section in the liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, the major liturgy in use today in the Orthodox world and produced early in the 5th Century, edited from earlier Syriac versions:

Remembering this saving commandment and all those things which have come to pass for us: the Cross, the Tomb, the Resurrection on the third day, the Ascension into heaven, the sitting at the right hand, and the second and glorious coming.

My take on that prayer is linked above.

Since Conley did not provide links to Vaughn, I found the latter in Facebook and asked him for his original. He told me it is now lost, however he added that in it he had included more from Chrysostom and others, than what Conley had acknowledged.

I had recently retrieved from storage my English version of the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, after being there for almost 10 years, so I went and checked where Vaughn told me and lo! There, bookmarked, were more bits ad pieces suggesting Preterism. I had bookmarked them years ago, but had forgot about them! Pages 71, 73 and 74 of the 1984’s edition of St. Tikhon’s Seminary Press read:

Thou it was who brought us from non-existence into being and, when we had fallen away, didst raise us up again, and did not cease to do all things until Thou hadst brought us up to heaven, and hadst endowed us with Thy Kingdom which is to come.

The final qualifying phrase, which is to come, no doubt steers the prayer into the Futurist camp, however, how can a heavenly Kingdom that was already endowed to us after we were risen and brought up to Heaven, be future? Grammatically this is incoherent, so Conley, and the Orthodox in general, explain it mystically, saying that in the liturgy time and space cease to exist. I can attest that time and space are really lost at the liturgy, so it is a reasonable explanation, the best explanation, had we not have the numerous and unequivocal time statements from our Lord and his ambassadors, that everything was to be fulfilled soon, in that generation. If we acknowledge that the Kingdom is come and its nature is not of this material world, and while we are in this world that Kingdom is within our hearts, we would be able to lose the earthly notion of time and space and commune with the spiritual realm more often, with more conviction, anywhere.

Moreover, if we remove the ending phrase which is to come we would have a full Preterist statement. Prayers, liturgies and confessions of faith have been edited and changed more than once. I have no direct evidence and this is speculation, but it is within the realm of the possible, that the futurist majority or the politics of the time demanded its inclusion and thus it came to us as it is.

Furthermore:

Who, when He had come and had fulfilled all the dispensation for us, in the night in which He was given up- o rather, gave Himself up for the life of the world-

If all dispensation is fulfilled, then, well, a mystic approach is the best way to explain why it really has not been fulfilled. Whether all was accomplished in 66-70 AD or at the cross, is beyond the scope of this article. In a way the cross was the end of the dispensation as it was the main part of its ending process, everything else, as per the Lord and the apostles, was to be fulfilled soon, in that generation.

The question is:

Is all the dispensation fulfilled or is it not?

No matter how much mystical Now, but Not Yet, for the Futurists, all is not fulfilled yet, contrary to the statement of the Saint’s liturgy.

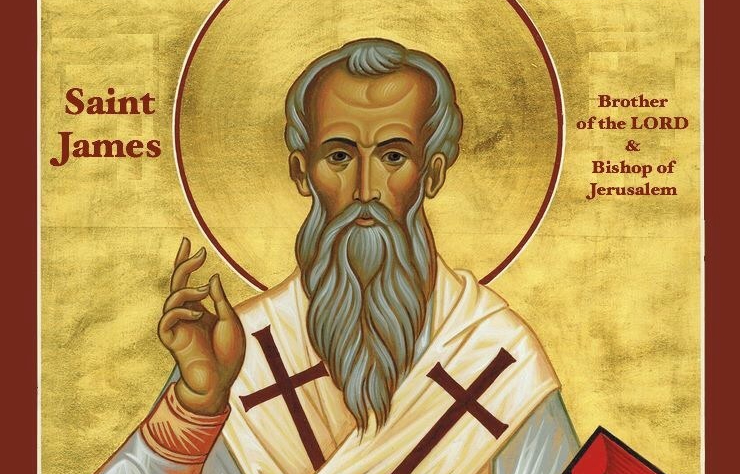

Even more shocking to me was what Vaughn mentioned about the liturgy of Saint James. The Orthodox admit that it was composed by the brother of the Lord himself, so it predates 70AD. Its Anaphora reads:

Do in remembrance of Me when you partake of this sacrament, commemorating My death and My resurrection until I come.

Your death, our Lord, we commemorate, Your resurrection we confess and Your second coming we wait for.

While we remember, O Lord, Your death and Your resurrection on the third day, Your ascension into heaven, Your sitting at the right hand of God the Father and Your second coming whereby Your will judge the world in righteousness and reward everyone according to his deeds.

The Anaphora of St James, which as per Orthodox affirmation, predates 66-70 AD, hence preceding the end of the age as full Preterists see it, has all eschatological statements in the future tense. On the other hand, the Anaphora of St John Chrysostom, composed in the 5th century, well into the new age as per full Preterists, has all eschatological statements, save one, arguably in incoherent manner, in the past tense.

Dear reader, judge yourself by the facts. These are questions that need to be answered. In my humble view the best answers are found if we assume that He has fulfilled all the dispensation. Many of the fathers, must have intuitively known this and tried to express it, knowingly or unknowingly, but a dominant culture is a dominant culture and often its influence is overarching.

Lord Jesus Christ son of God, have mercy on us, sinners!

One may observe that St. Luke records that the apostles gathered daily in the Temple precincts, the Porticos of Solomon, opposite the Mount of Olives, to recollect “The Prayer” (i.e. the Anaphora or Eucharistic canon); see Acts 5:12, 2:42. There they prayed and “many priests” of the temple joined them (Acts 6:7). One may indeed wonder if the Descent of the Holy Spirit was coincidental with the epiklesis of the first Mass that the apostles finally recollected rightly. At any rate, temple worship would have insinuated itself into Eucharistic prayer as naturally as the primal Seder had influenced Jesus Passover Sacrifice. One may foresee that Yom Kippur affected the Eastern liturgies more than the Western, which were more bound to the Passover. But when the Temple fell, only the Eucharistic sacrifice remained by which the people of the covenant could worship God, and by which the faithful dead could be bodily bound up to the resurrected Christ. Hence, the Eucharist emerged even as the bodily incursion of the saints into the assembly of the penitential sinners. The glory to come, comes.

Amen.